Authors:

Mona Makhlouf & Ashley McKenzie

Motivation is an internal feeling that directs people’s behavior towards a particular direction to complete a given task and energizes them to continue to succeed. Ormrod stated that "Motivation is the inner state that energizes, directs, and sustains behavior." Not all students are motivated in the same way. Some students feel independently motivated to know subject matters and seek out the challenge to learn more about the concepts in the subject areas they study. However, others feel more motivated when their teachers use external motivators such as certificates or recgonize their names in classrooms (Ormrod, 2000). These two forms of motivation are intrinsic and extrinsic. Some students feel extrinsically motivated when they get good grades, receive money, or are awarded. Others feel intrinsically or self motivated to develop a skill and acquire knowledge in a specific content area that suits their interests. Extrinsic motivation is not a bad thing to foster in classrooms, but rewarding students all the time for every task may erode their intrinsic motivation and make them begin working for the reward and not for their love of learning which could endanger their ability to succeed throughout their lifetime.

Original page: http://www.electrical-res.com/intrinsic-extrinsic-motivation/

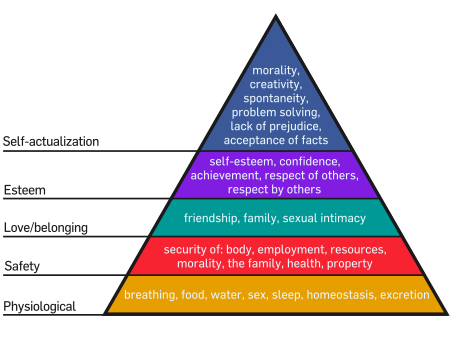

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a theory in psychology, proposed by Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper A Theory of Human Motivation. Maslow's hierarchy of needs, portrayed in the following shape of a pyramid, organizes the largest and most fundamental levels of needs at the bottom, and the need for self-actualization at the top. Raffini stated that the intrinsically motivated students seek autonomy, self-esteem, a sense of belonging, and stimulation (1996).

Image retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.…erarchy_of_Needs.svg

Image retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.…erarchy_of_Needs.svg

Snowman & McCown (2012) suggest teachers can meet student’s safety and belonging needs, as defined by Maslow, by learning students’ names as quickly as possible, praising students when they do well and inquiring about possible problems when they don’t, relating lessons to student’s interests, and never ridiculing a student for lack of knowledge or skills or letting other students do the same.

What does "Motivation" look like inside and outside classrooms?

Students will be more motivated to learn in the classroom if they are an active part of the lessons and classroom procedures. Each student could have a daily or weekly job to feel that s/he connected with other people in some way. For example, giving students chores (teacher helper, paper distributor, or door holder) motivates them to act efficiently and respond positively to their classmates. During lessons, instead of lecturing at students or having them fill out a basic worksheet, putting them in charge of part of the instruction will allow them to play the teachers’ role. Students feel motivated when they are engaged in meaningful activities as they realize how the things they learn in classrooms relate to their personal experiences, interests, abilities, and goals. By this way, they feel eager to pursue these topics further and develop their skills more to enable them to succeed. However, when students are given meaningless tasks, they feel frustrated and thus they avoid doing them as often as possible.

Why/What do teachers need to know about "Motivation"? Why is it significant to them?

Teachers must be aware of their students’ abilities and adapt their instructional strategies to match their students’ learning styles. Reid (1999) claims that this effort leads to, "higher interest and motivation in the learning process, increased student responsibility for their own learning, and greater classroom community" (p.300). This awareness and adaptation will intrinsically motivate students to learn. The theory of multiple intelligences helps teachers to investigate these different learning styles. The theory of multiple intelligence was proposed by Howard Gardner in 1983 as a rationalist model of intelligence that differentiates intelligence into various capacities for solving problems. Therefore, teachers should study the students’ abilities and intelligences, analyzing them as audio, visual, lingual, musical, or kinesthetic. Afterwards, teachers can adapt their lesson plans, classrooms activities, and their instructional strategies accordingly to better accommodate students’ intelligences. Arnold and Fonseca (2004) suggest that, "MIT in the EFL ... enables teachers to organize a variety of contexts that offer learners a variety of ways to engage meaning and strengthen memory pathways; it ... can increase the attractiveness of language learning tasks and therefore create favorable motivational conditions" (p.120). Teachers motivate their students by setting reasonable expectations to meet which require students to use their diverse abilities while also giving them opportunities to make choices to reach these expectations. On the other hand, it is necessary for teachers to be selective about when and how to use extrinsic reinforcers. When teachers reward their students excessively, it erodes their intrinsic motivation as they are doing their work for the sake of the reward and not for learning (Deci, 1999). Depending on the rote learning kills the meaningful learning and the students’ intrinsic motivation.Rote learning doesn’t help the students to understand a subject but instead it focuses on memorization through drill and kills technique.

This following video includes strategies for teachers to handle students with different intelligences in classrooms activities to meet their needs and various abilities.

http://www.primarily-kids.com/multiple_intell...

image retrieved from: http://wzpo1.ask.com…le_intelligences.jpg

Why do parents need to know about "Motivation"?

It is important for teachers to get parents involved in their children’s learning. It’s well observed that students whose parents are involved in school activities have better attendance records, higher achievement, and more positive attitudes toward school. Teachers must give suggestions to parents about learning activities they can easily do with their children at home. Teachers may also help parents to get a better idea about their children’s learning styles in order to use effective teaching strategies at home and address the students’ weaknesses. When parents are willing to work with their children at home, students will be automatically motivated to participate effectively in class activities. On the other hand, teachers should tell parents not to neglect or ignore their children because this will lead to low self-esteem, poor social skills, and low school achievement. Consequently, students may feel depressed, anxious, and socially withdrawn in school.

How does "Motivation" concern students?

Students’ emotions play a role in their learning and achievement as well. If students are engaged in topics related to their real life situations, they will feel motivated to learn more because they realize value and purpose behind studying the lesson. When students notice the relationship between the topics they learn and how they answer to some of their life mysteries, they will be eager to pursue those topics further. Also, if they find that the assigned homework or activities often lead to more frustration than pleasure, they will avoid being engaged in the assigned tasks. Students feel more self-motivated when they are engaged in meaningful activities as they realize how the things they learn in classrooms relate to their personal experiences. For language learners, motivation stemming from a disire to communicate with people from another cultural group, combined with communication competencies and self-confidence, plays a defining role in their willingness to communicate (MacIntyre, 2007); without this willingness they may never be able to fully use the target language.

Robert Harris (2010) stated some ways for motivating students at different ages:

- Explain. When students do poorly on assignments or participation, it is often because they do not understand what to do or why they should do it. Therefore, teachers should spend more time "explaining why we teach what we do, and why the topic is important and interesting". Teachers' enthusiasm will be transmitted to the students, who will be more likely to become interested. In addition, teachers should spend more time explaining exactly what is expected on assignments or activities. "Students who are uncertain about what to do will seldom perform well". Students should understand the objective of learning new concepts in order to speak to the question they often ask, "When will we ever use this?” This helps the students learn to connect studying concepts in classrooms with using them in real life situations, fostering students’ intrinsic motivation to discover and learn more about the topics rather than only temporarily motivating (extrinsically motivating) them to get a good grade or to be promoted to the next grade level.

- Reward.Students who are not internsically motivated should be helped by extrinsic motivators in the form of rewards. Instead of criticizing unwanted and unacceptable behavior or answers, teachers should reward the correct behavior and answers. The rewards should be configured to the level of the students such as giving stickers or a set of crayons for young children. At the college level, professors have given certificates, exemptions from final exams, and verbal praise for good performance. The important point is that extrinsic motivators can, over a brief period of time, produce intrinsic motivation. It is absolutely true that everyone likes the feeling of accomplishment and recognition; rewards for good work produce those good feelings.

- Use positive emotions to enhance learning and motivation. People remember better when the learning is accompanied by strong emotions. Teachers could make the learning experience successful by letting them have fun, grow excited, and feel happy and motivated. Emotions can be created in classrooms by doing something unexpected and unordinary to keep students ultimately motivated to complete their tasks successfully.

- Have students participate. "One of the major keys to motivation is the active involvement of students in their own learning". Standing. Getting students involved in activities and group problem solving exercises is highly recommended to let the students actively participate in the lesson rather than simply looking at pictures or listening to the teacher. A lesson about nature, for example, would be more effective through doing the work than by only looking at pictures.

- Teach Inductively. When teachers present conclusions first and provide examples, it helps students to feel the joy of discovery and make them more excited to learn. Therefore, teachers may introduce the new topic to their students by asking them questions about the topic they learn to help them to make sense of the newly introducted concepts. This will help students to draw conclusions themselves by giving stories and then arriving at conclusions later, which increases their interests and motivation as well.

References:

Arnold, J. & Fonseca, M. C. (2004). Multiple intelligence theory and foreign language learning: A brain-based perspective. International Journal of English Studies, 4(1), 119-136.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Garderner & Lambert. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House

Huitt, W. (2007). Maslow's hierarchy of needs; educational psychology interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University.

Macintyre, P.D. (2007). Willingness to communicate in the second language: understanding the decision to speak as a volitional process. The Modern Language Journal, 91(4), 564-576. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4626086

Maslow, A. H. (1987). Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper & Row.

McCown, R., & Snowman, J. (2012). Psychology applied to teaching (13th ed.). China: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Ormrod, J.E. (2000). Learning and cognitive processes in educational psychology; developing learners

Raffini, J.P. (1996). 150 ways to increase intrinsic motivation in the classroom. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Reid, J. (1999). Affect in the classroom: Problems, politics, and pragmatics. In J. Amold (Ed.) Affect in language learning (pp.297-306). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Additional references:

Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4), 370-396.

Hilgard, Ernest., R. Irvine. (1953). Rote memorization, understanding, and transfer: an extension of Katona's card-trick experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 46 (4), 288–292.

Schweinle, A., Turner, J.C., & Meyer, D.K. (2006). Students’ motivation and affect in elementary mathematics. Journal of Educational Research, (99), 271-293.